Lately, like so many others, I've been completely consumed by the whims of our present moment. So much is happening that, on some days, I've felt like a fish washed up on shore – flailing and gasping for... what? Air?

But it has also been necessary to shift focus. Even though I now also feel it's time to let go. Partly because the issue is on everyone's lips anyway, and partly because there are so many more knowledgeable and better portrayers of the daily antics than me. My contribution here has mostly been to try to get an overview by gathering many different perspectives, knowing that nothing is simple, which has perhaps been my main merit – or is – we will have to see.

What interests me more is to lean back just a little and try to get a glimpse what lies beneath the surface. And when I don’t do that – then it feels like I’ve lost my soul.

Or maybe it's not me who feels that way in the first place, but rather a feeling aroused by the thought that you might perceive it that way; that is, as if I had lost my soul.

Let’s shift now, in light of whatever it is I (or perhaps you) feel has been lost. That soul of mine.

Most of us have no trouble understanding words like screw, donkey, or doorknob. Nor do we usually struggle with terms like exaggerated, interactive, or foolhardy. But once we start dealing with more abstract words, things quickly become more complicated.

Such words often carry a haziness or arbitrariness – precisely because they allow for so many meanings. Difficult and abstract terms can easily become exclusive, yet at the same time, they have a strange ability to bind us together.

It's often in odd communities that the most elusive expressions arise – phrases that carry meaning only within the group and function as a kind of linguistic glue. Among specialists, this might involve technical terms; among religious groups, more esoteric concepts that, to outsiders, can sound like utter gibberish: ditthupâdâna, trinity, takfir.

You could say that every community builds its “we” through the words they use.

But then we have those words that all of us constantly use – yet hardly anyone knows what they actually mean. Words that act more like signs or symbols, surrounded by a whole sphere of loosely connected associations.

Which brings us back to my lost soul.

And the question we must ask here is: What exactly is it that I – or perhaps you – feel has been lost? Is it my voice? My probing reflections? Or something else entirely? What does it even mean to say that someone has lost their soul? Does it mean they have lost their mind? Well, I guess it depends on how we use that particular term 'soul'.

When it comes to ambiguous words like soul – and, for that matter, spirituality – it’s probably best to lean in a little closer and really listen to what’s being said. These concepts are so vast that without careful attention, it’s difficult to grasp their true substance – or spirit, so to speak.

Because there’s something truly distinctive about words like soul and spirit – especially since they appear in virtually every language.

Take the word spirituality. In some circles, it refers strictly to a religious mindset, often reserved for the devout. In other contexts, it describes something more universal, something all humans are said to share.

People speak of spiritual strength, spiritual renewal, our spiritual abilities. Among philosophers, one encounters phrases like the phenomenology of spirit; among humanists, talk of human spiritual development. And the deeper you dig into all these variants, the harder it becomes to determine what this spirit actually consists of.

When the words are used, they usually point to a kind of non-substance – something immaterial, yet still considered very real. For some, it’s closely tied to what they call “god” – and which they often spell with a capital G. There’s a historical link here between the two terms.

(Incidentally, another metaphysical framing still lingers in surprising places. The English word spirits, used for strong alcoholic drinks, comes from the same Latin root spiritus. In early distillation practices, the vapor was thought to be the 'spirit' or essence of the substance – its purified breath. That’s why!)

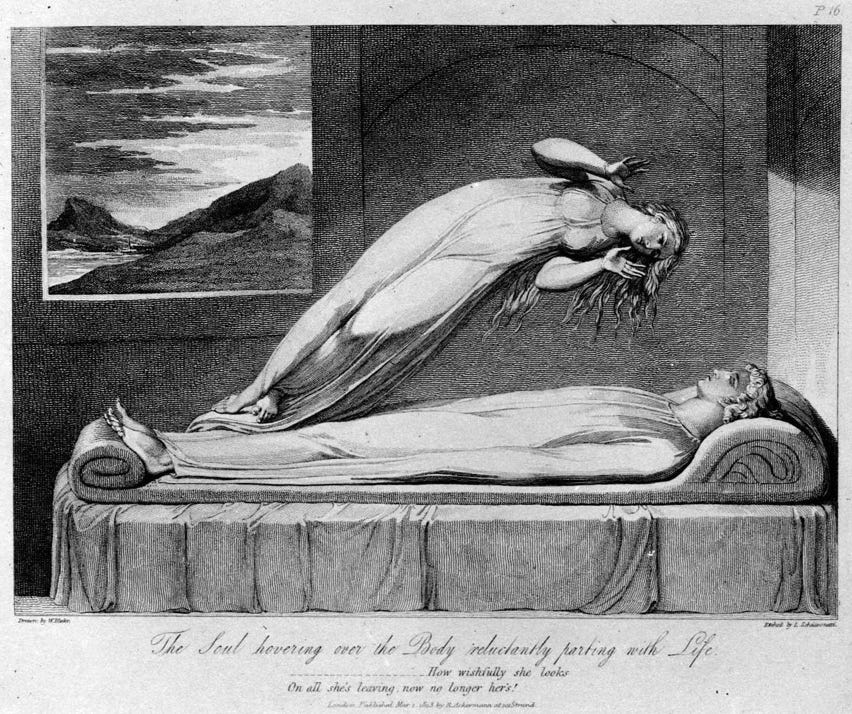

But where do all these ideas come from? Where did this spirit that we’re all supposed to contain first arise? The one said to leave the body when we die. The one said to set us apart from animals – at least according to the French philosopher René Descartes.

Someone once tried to weigh it and concluded it weighs 21 grams. Freud tried to analyze it – by having it lie down on the couch. But were they even talking about the same “spirit”?

Still, if we’re being honest... spiritually, spirit – it even sounds like it has something to do with breathing (espirare – respirator).

And maybe that’s exactly how the idea of this spirit was born. Consider the English word spirit, which comes from Latin spiritus, meaning breath or air. Follow that thread further back, and spiritus was a translation of the Greek psyche – the root of psychology, the study of the soul or the spiritual faculties of the human being. And psyche, in turn, comes from the root bhes, which in ancient Sanskrit means life – or yes, breath.

Look to the Semitic languages and we see the same pattern. In Arabic, a distinction is made between nafs (self, desire) and rūḥ (spirit, divine inspiration). In Hebrew, a similar distinction appears: neshama and nephesh on one side, and ruachon the other. Neshama comes from the root NŠM – meaning “to breathe” – while ruach means wind, spirit, motion.

Here too, breath seems to be the key – both to life and to the mysterious force that separates the living from the dead.

And this pattern shows up again and again.

In the Indian word Mahātmā, which means “great soul,” we find the suffix ātman. Ātman (Atma, आत्मा, आत्मन्) is Sanskrit and means essence, soul – or yes: breath. In Hinduism, ātman is part of Brahman, the highest godhead or the universal whole. The word comes from an ancient Indo-European root meaning “to breathe” – the same root as in the German word atmen, which still means “to breathe.”

In some traditions, the breath remained simply a bodily function; in others, it became the gateway to the soul’s mystery.

In Uralic languages like Finnish and Hungarian, the words for breath (hengittää, lélegzik) come from the same root as those for soul (henki, lélek). In Russian, both dyshat’ (to breathe) and dukh (spirit) share the same root.

In Chinese, the life-giving force is called qì – a word meaning both “air” and “vital energy.” In Māori, hā means breath, but it’s also the word for spirit. One speaks of living within hā o te ora – the breath of life. We live in air – breathe in and breathe out – until one day, we no longer do so.

Across language families, again and again, humanity has let the act of breathing become the very metaphor for life – and the thing that departs when we die. Breathing isn’t just a biological function; it’s also a linguistic witness to our ideas about our spirits.

For a long time, the air we breathed was considered the finest and most ethereal substance we knew. As long as breath flowed from mouth and nose, one lived. When it stopped – life ended – and the spirit left the body.

Could it be that our soul was born - the moment we became aware of our own mortality? It is so wondrous that it almost takes your breath away.

Wow! You're asking some interesting and important questions here. And you've done some impressive research into all those different languages. In Arabic, nafs is also used in the sense of soul, psyche, essence, individual, essential truth, mind, one's own opinion... and the verb formed from the same root (tanafas, 5th tribe) means to breathe, sigh. From the root ruh we also have the word riha, which means scent, aroma (things you breathe in)